Home>Artificial Intelligence and the Labor Market

19.03.2024

Artificial Intelligence and the Labor Market

Written by Katarina Milanovic, Research Assistant for the Women in Business Chair

Recent debates have focused on Artificial Intelligence’s (AI) potential effects on the labor market and economic growth. While the ever-growing innovation in AI research carries the promise of increased productivity and new job creation, some specialists worry about potential job losses and rising inequalities. Earlier in 2023 for example, a Goldman Sachs report stated that while generative AI could create new jobs and boost global productivity, it could also lead to a “significant disruption of the labor market”, with an estimated 300 million jobs exposed to automation. Another example is that of British Telecom’s announcement of its plans to cut as many as 55,000 jobs by 2030, with the potential to replace 10,000 of those jobs with AI.

Furthermore, AI use could disproportionately and negatively impact the socio-economic groups that have historically faced the most obstacles on the labor market. Academics are increasingly calling for analyses of AI that would specifically examine gender and racial biases (see Khan, 2023, and Gomez-Herrera and Köszeg, 2022). While the risk of intelligent automation is predicted to transform most occupations to a certain degree due to the rapid increase in generative AI’s ability to perform non-routine cognitive tasks, recent reports addressing the gendered effects of AI highlight occupational segregation as a recurring area of concern (Gomez-Herrera and Köszeg, 2022; Lane and Saint-Martin, 2021).

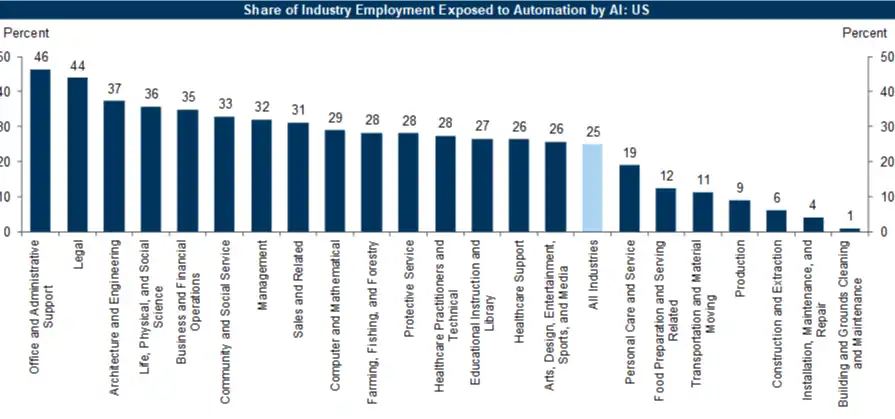

The direct effect of AI on pre-existing jobs depends on whether the new technology is a complement or substitute to workers’ skills. For example, new developments in AI technology may serve as a complement to a radiologist analyzing medical scans (Gopinath, 2023), but replace the need for administrative employees whose main tasks are comprised of patient information data entry. The former would thus experience an increase in productivity of their job, while the later would likely find most of their tasks replaced by AI and thus face a much higher risk of job loss. Automation itself is nothing new – task replacement and job transformation follow periods of technological innovation of the past. For example, the car manufacturing industry has seen a decrease in the use of manual assembly lines with the development of robotic arms. While past automation had been restricted to routine tasks, generative AI’s ability to conduct non-routine cognitive tasks exposes previously insulated professions, formerly considered as complements to automation, to substitution. The following graph, taken from recent research from Goldman Sachs, shows the estimated share of employment at risk of automation by generative AI for certain industries in the USA, and can be indicative of future changes in the labor market caused by AI.

In-here lies the potential for an unequal distribution of the job displacement burden between men and women, with research still lacking a clear answer. Prior to the development of generative AI, several past studies identified manufacturing industries as most at risk of automation replacement technologies (Collett et al., 2022). Given that men are more concentrated in these industries, men appear to have been the most exposed to automation-related job displacement (Collett et al., 2022). On the other hand, Brussevich et al. (2019) found that on average, across all sectors and occupations, women performed more codifiable and routine tasks than men, resulting in higher risk of job displacement due to automation for the former group. Generative AI has further complicated efforts in predicting clear future gendered effects on the labor market. Some recent reports have identified clerical and service work as most susceptible to AI replacement, and The Effects of AI on the Working Lives of Women report cites a recent study finding that women make up 70% of the clerical and administrative workforce in the US. Another study focusing specifically on financial services finds that women hold only 25% of senior management positions, typically considered to have the lowest risk of AI replacement. This suggests that positions within the financial sector most insulated from AI automation are concentrated among men (Collett et al., 2022). While research on gendered differences in outcomes remains context specific, it is clear that without proper policies targeting AI implementation and adequate reskilling of workers, the increased use of AI creates a large possibility of exacerbating gender inequalities in the labor market.

AI has also the potential to increase barriers to entry for new generations of the workforce through unequal access to education and opportunities that generate AI complementary skills. The 2018 OECD report on Bridging the Digital Gender Divide finds that in most OECD countries, women are less likely to hold high levels of “digital literacy” compared to men, and that this difference grows larger with age, as skill development becomes much more challenging with simultaneous employment and domestic care responsibilities (Collett et al., 2022). The gender difference in early stages of career development can be linked with differential sorting into education fields, despite similar interests and abilities in early childhood (Gomez-Herrera and Köszeg, 2022), and this discrepancy is often credited to socialization, self-confidence, and traditional gender norms (Collett et al., 2022). The She figures 2021 report conducted by the European Commission found that in Europe, only 34% of STEM graduates are female, and only 17% of Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) graduates are female. The gender disparities in AI complementary skills and education generate unequal advantages in competitiveness on the labor market, particularly for jobs benefiting the most from AI innovation. The World Economic Forum’s 2018 Global Gender Gap Report found that globally, only 22% of AI professionals are women. Without addressing the social and economic barriers to education and skill development faced by vulnerable groups, including women and young girls, the increased use of AI could reinforce gender stereotypes and occupational segregation in the long-run.

The initial reduction in labor demand in highly automated fields could potentially lead to a resurgence of traditional gender norms, as speculated by Alice Evans, Senior Lecturer at King’s College London, in her article titled Are Robots Replacing Women?. With a surplus of skilled workers and a new constraint of job availability due to AI implementation, some profitable companies might find it easier to maintain any existing taste for discrimination. Apart from crowding out women from certain jobs, a more skewed gender ratio may reinforce traditional gender norms, potentially creating a negative feedback loop for future generations.

Finally, AI technologies themselves can be inherently biased if trained on data that is unrepresentative of society, or if designed by a team lacking diversity and thus subject to unconscious biases and stereotypes. In both cases, groups that have been historically excluded from data collection and inclusion in analyses would be disproportionately affected by AI biases. Related to the labor market, this could introduce biases and discrimination in hiring systems and intrusive monitoring systems. For example, in 2018, Amazon implemented an AI hiring system that it had to abandon due to gender biases. Due to the data it was fed, the algorithm trained itself to penalize resumes that contained the word “women’s”. Concerns about the reinforcement of traditional stereotypes through AI bias have arisen, as in the case of the feminization of virtual assistants (Collett et al., 2022). Virtual personal assistants (VPAs) with feminine voices may promote the association of women with care and supporting roles. Furthermore, VPAs themselves have been targets of gender based harassment and verbal abuse. In 2020, one of Brazil’s largest banks registered 95, 000 morally or sexually offensive messages to their feminine AI Chabot. UNESCO’s I’d Blush if I Could report emphasizes that cases like this could lead to the normalization and tolerance of verbal abuse and harassment of women in daily life (West et al., 2019; Collett et al., 2022).

Although the future of AI in the labor market is uncertain, the above paragraphs present a strong case that without careful research and the creation of effective policies, existing inequalities could worsen. Recent reports highlight the importance of “good policies”. For instance, Brynjolfsson and Unger (2023)’s article The Macroeconomics of Artificial Intelligence emphasizes a significant gap between the research advancing AI technology and research understanding its economic and social impacts. They caution against viewing the future of AI as predetermined, but that it rather depends on policy decisions. They call for “innovations in economic and policy understanding that match the scale and scope of the breakthroughs in AI itself”, stressing that the “bad future” is the path of least resistance. With policymakers shifting their perspective to focus on how AI can complement human labor rather than replace it, they believe that society has the power to collectively shape the unpredictable future of AI.

The push for rigorous policymaking and caution in the implementation of AI is fueled by research that has yet to produce conclusive results on the effects of AI. The fundamental method of economic estimation relies on using data to estimate ex-post the effects of an event from the past. Given that we are still in the phase of rapid AI development, researchers are faced with two obstacles: insufficient data availability for their estimations, and not enough time passed for effects to materialize. Furthermore, the unprecedented advances in AI’s ability to perform non-routine cognitive tasks sets it apart from any period of rapid technological change observed in the past. While the long-standing belief within neoclassical economics is that any form of technological innovation leads to an increase in productivity, which leads to an increase in income, economic gains, and the betterment of living standards, the novelty of generative AI poses a significant obstacle in forecasting the future. In particular, beliefs and projections about adequate redistribution of the gains of AI and its effects on unemployment rates during the economic adjustment period remain ambiguous (Stevenson, 2018).

Nonetheless, a common message arising from new research and academic discussions on automation and AI is the importance of straying away from binary stances, like doomsday or utopia, which have become common narratives in popular press and academic circles. In Artificial Intelligence, Automation, and Work, Acemoglu and Restrepo (2018) develop a framework to address this false dichotomy in beliefs, which is centered on balancing mechanisms. While automation, AI and robotics can replace workers in tasks that they previously performed, reduced production costs, increased capital accumulation, and increased productivity of machines could offset this replacement. Furthermore, the creation of new tasks can directly counterbalance the initial job displacement. The researchers’ framework emphasizes the role of firms, workers, and other actors within society in deciding the speed and nature of both advancements within automation and the creation of new tasks.

To better identify the various labor market effects more specific to generative AI, there has been an increasing focus on task-based theory models within research. Task analysis allows for a more precise identification of the extent to which roles will be reduced, expanded, or rendered obsolete due to AI, by considering variation within a given occupation. Agrawal et al. (2019) use the task based approach in their article Artificial Intelligence: The Ambiguous Labor Market Impact of Automating Prediction, where they propose a distinction between prediction tasks and decision tasks. By distinguishing the tasks as such, the authors are able to demonstrate that the impact of AI on jobs depends on whether prediction automation will be a complement to or replacement of the given tasks. They emphasize that the theoretical net effects are ambiguous, and that the impact of AI introduction on employment and wages depends on specific empirical contexts. For example, a recent empirical working paper by Hui et al. (2023) studies the release of ChatGPT in the context of an online labor market of freelancers offering services most substitutable with ChatGPT’s capabilities: writing, editing and proofreading. The results of this paper show a reduction in the short-term demand for, and wages of, remote freelancers of these highly affected tasks compared to those providing less affected services. A similar reduction was found for remote freelancers offering design, image editing, and art services when estimating the effects of the release of image-generating AIs, such as Dall-E and Midjourney. The large heterogeneity in empirical evidence is apparent when observing newer firm-level analyses, which do not support that automation has a negative effect on overall employment and wages when allowing for an adjustment period (Lane and Saint-Martin, 2021). However, much of the empirical research remains focused on robotization and automation, so there is still a need for more analysis specific to generative AI’s impact on labor outcomes. Furthermore, the possibility of lagged effects generates a need for caution of AI implementation and a continuous research effort as new data becomes available.

The discussion around AI has evolved from theoretical debates to practical considerations of how generative AI is revolutionizing society. The increased use of AI in various sectors has generated both excitement and concerns. These concerns include issues related to misinformation, job displacement, income inequality, biases, and societal stability (Bhatt, 2023). Collaboration between various stakeholders, including governments, industry, academia, and civil society, is seen as crucial in shaping the future of AI and ensuring inclusive and sustainable social and economic progress.

References

Acemoglu, D. and Restrepo, P. (2018). Artificial intelligence, automation, and work. In The economics of artificial intelligence: An agenda, pages 197–236. University of Chicago Press.

Agrawal, A., Gans, J. S., and Goldfarb, A. (2019). Artificial intelligence: the ambiguous labor market impact of automating prediction. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 33(2):31–50.

Bhatt, G. (2023). The ai awakening. Finance & Development, 0060(004), A001. Retrieved Jan 9, 2024, from https://doi.org/10.5089/9798400260179.001.A001

Brussevich, M., Dabla-Norris, M. E., & Khalid, S. (2019). Is technology widening the gender gap? Automation and the future of female employment. International Monetary Fund.

Brynjolfsson, E. and Unger, G. (2023). The Macroeconomics of Artificial Intelligence, Finance & Development, 0060(004), A006. Retrieved Jan 9, 2024, from https://doi.org/10.5089/9798400260179.001.A006

Collett, C., Gomes, L. G., Neff, G., et al. (2022). The effects of AI on the working lives of women. UNESCO Publishing.

European Commission, Directorate-General for Research and Innovation, (2021). She figures 2021 : gender in research and innovation : statistics and indicators, Publications Office. https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2777/06090

Gomez-Herrera, E. and Köszegi, S. T. (2022). A gender perspective on artificial intelligence and jobs: The vicious cycle of digital inequality. Technical report, Bruegel Working Paper.

Gopinath, G. (2023). Harnessing ai for global good. Finance & Development, 0060(004), A018. Retrieved Jan 9, 2024, from https://doi.org/10.5089/9798400260179.001.A018

Hatzius, J. (2023). The Potentially Large Effects of Artificial Intelligence on Economic Growth (Briggs/Kodnani). Goldman Sachs.

Hui, X., Reshef, O., & Zhou, L. (2023). The short-term effects of generative artificial intelligence on employment: Evidence from an online labor market. Available at SSRN 4527336.

Khan, R. (2023). We need a global feminist campaign against artificial intelligence bias. Media@ LSE.

Lane, M. and Saint-Martin, A. (2021). The impact of artificial intelligence on the labour market: What do we know so far?

Stevenson, B. (2018). Artificial intelligence, income, employment, and meaning. In The economics of artificial intelligence: An agenda, pages 189–195. University of Chicago Press.

West, M., Kraut, R., & Ei Chew, H. (2019). I'd blush if I could: closing gender divides in digital skills through education.

World Economic Forum (2018), The Global Gender Gap Report 2018 https://www.weforum.org/publications/the-global-gender-gap-report-2018