Ukrainian threefold revolution: from Soviet Ukraine to European Ukraine?

Background of the protests

Euromaidan revolution – it is a logical continuation of the deep social and political transformations that began in Ukraine in 1991.The implosion of the Soviet Union was widely perceived as an ideological triumph of democracy over authoritarianism. Optimistic expectations foresaw that autocracies would be transformed into functioning democratic states, but many regimes in the post Soviet area have either remained hybrid or moved in an authoritarian direction. As mentioned Steven Levitsky and Lucan Way: “the collapse of one kind of authoritarianism yielded not democracy but a new form of nondemocratic rule”1.

During more than two decades, Ukraine belongs to the countries which are mixed a form of democracy with a substantial degree of illiberalism. It is hardly surprising then that Ukraine lays far behind in the post-communist transition, especially in the light of the following factors: the long process of ‘Sovietization’; the very limited positive impact of international factors; and the very negative impact of local elites (mostly inherited from the Communist past).

The oligarchic, deeply corrupted system in Ukraine was firmly established at the end of the 1990s, during the rules of President Kuchma. It became clear that the post-Soviet nomenclature turned into oligarchy had no vested interest in democratization and real Europeanization, as this was likely to undermine its dominance over the country’s politics and the economy. At the same time, the oligarchic regime widely employed democratic and pro-European rhetoric.

The Orange revolution was an unsuccessfully attempt to destroy this system. Ongoing political conflicts and lack of the real reformation of the system led to huge disappointment and frustration of Ukrainian society.

There was a general and widespread public cynicism about government and politics, and about what the Ukrainian government’s commitments on paper mean in reality. There was a big difference between the “formal rules” and the way most political institutions actually worked in Ukraine.

Victor Yanukovych won presidential elections in 2010, mainly used this deep dissatisfaction by the ‘Orange’ team, because he promised to bring political stability and provide economic growth. President Yanukovych had insistently tried to centralize power since his election in 2010. In October 2010, Yanukovych used his influence over the Constitutional Court to repeal the political system reform of 2004 and restored the strong semi-presidential model. It gave to Yanukovych the same powers as president Kuchma previously had. At the same time, an unprecedented process of the executive becoming dominated by representatives of Party of Regions. Yanukovych tried “to transform Ukraine’s minimalist electoral democracy into an electoral authoritarian system2.” Despite of power consolidations his chance of winning another fair presidential election was unrealistic.

Euromaidan protests

The protests now well known as ‘Euromaidan’ started as a claim for European integration, but later turned out as a massive protest against regime of president Yanukovych and entire corrupted political system.

We can distinct the three phase of Euromaidan protests:

• ‘Euro-romantic’ stage (21 – 30 of November 2013)

• The ‘claim of justice’ (1 of December 2013– 16 of January 2014)

• ‘Reset of the system’ (16 of January – 22 of February 2014)

“Euro-romantic” stage

The Euromaidan protests started on Thursday 21 November 2013 as a demand for European integration. On the initial stage it was peaceful protests organized mainly by students, civic activists and young Ukrainians. Few days later it attract more people as a reaction against the refusal of Viktor Yanukovych and his government’ to sign the Ukraine-EU Association Agreement.

To those people, EU association appeared as a way out of corruption, cleptocracy and attempts to come back to authoritarian order by the Yanukovych`s team. As outline Alexander Motyl, for many Ukrainians “the European choice – it is not about only the dreams of European standards of life or real European integration of Ukraine, it is mainly about their hopes to change situation in the country, about basic civil rights – security, freedom of speech and possibility to make their own choice3.”

The scale of the protests was a surprise not only for authority but even for the oppositions. But it was not unexpected situation, because dissatisfaction of Ukrainians by the situation in country raised significantly in last year’s. In the May of 2013, the number of Ukrainian population who were ready to participate personally in protests was 27% (9% - "definitely" and 18% - "likely"). However, 36% of the population is not going to take part in the protests and demonstrations, 25% probably will not take part. Compared with October 2012 the number of people willing to protest, increased by 5% and significantly reduced the number who exactly will not take part in the protests - from 51% to 36%4.

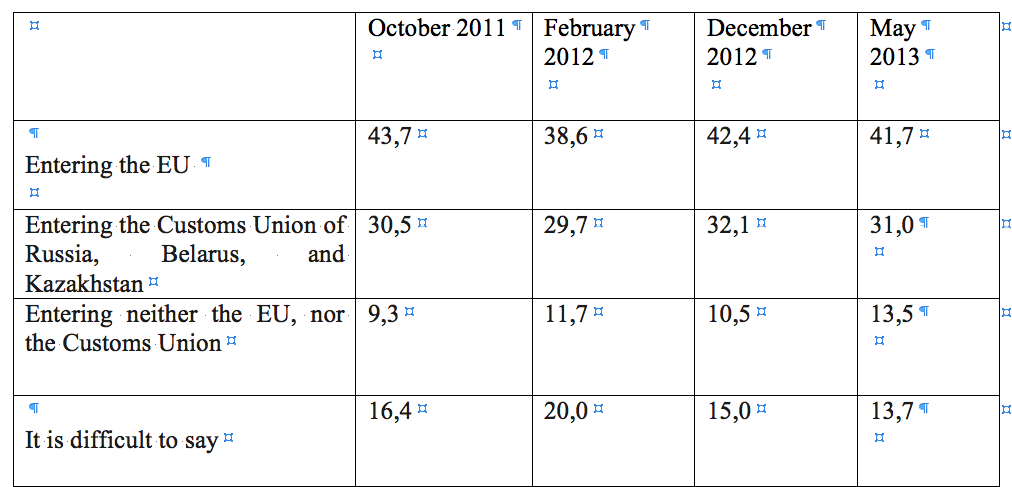

The topic of European integration was also debated issue, and reflects different vision of Ukrainians of further development of country. According to opinion poll surveys, since 2011 public support for the European integration has been prevailing over support for integration into the Customs Union.

Table 1

In which direction of integration should Ukraine move? In %

Source: Zolkina M. European integration of Ukraine: experience of yesterday for development of tomorrow. Ilko Kucheriv Democratic Initiatives Foundation, Public Opinion, n° 13, 2013:4.

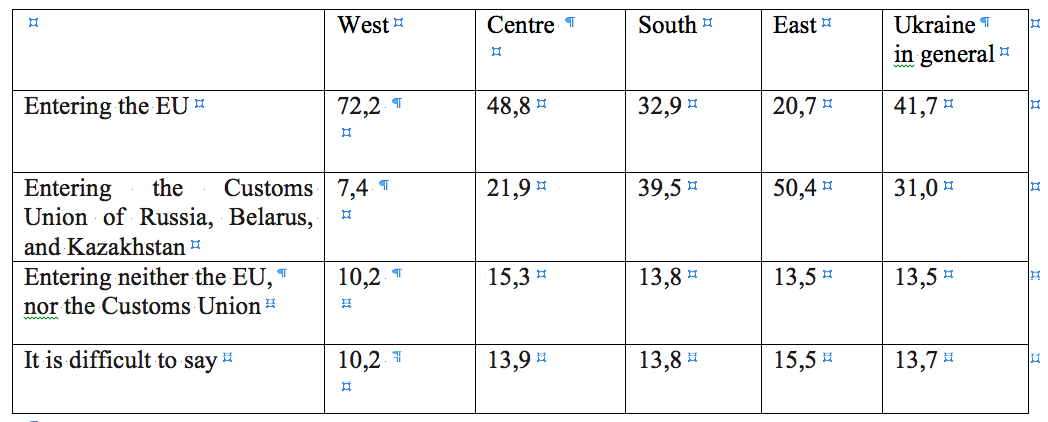

Distinctive features of public attitude towards the European integration have rather stable and clear region–and age–specific differences.

Table 2

In which direction of integration should Ukraine move? In %

Source: Zolkina M. European integration of Ukraine: experience of yesterday for development of tomorrow. Ilko Kucheriv Democratic Initiatives Foundation, Public Opinion, n° 13, 2013:6.

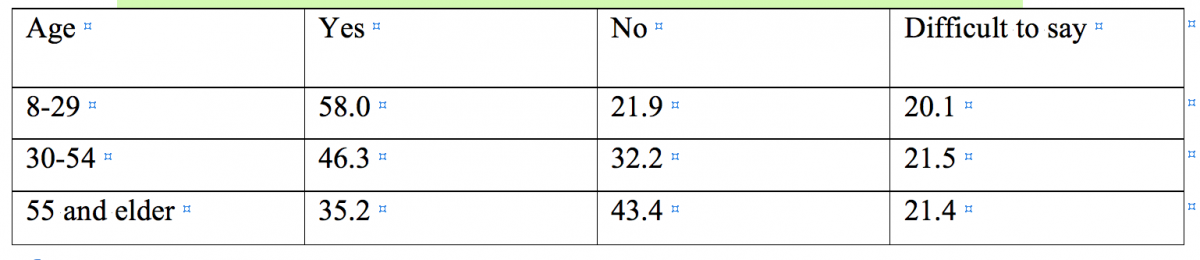

Table 3

In which direction of integration should Ukraine move? In %

Source: Zolkina M. European integration of Ukraine: experience of yesterday for development of tomorrow. Ilko Kucheriv Democratic Initiatives Foundation, Public Opinion, n° 13, 2013:6.

In fact, Ukrainians want to ‘have it all’, as evidenced by simultaneous support for closer integration with the EU and Russia by approximately one third of the Ukrainian population. These multi-directional preferences suggest that even though the public is keen on European integration, it sees no contradiction between seeking EU membership and closer political and economic ties with Russia5.

The ‘claim of justice’

On the night of 30 November 2013 the special police unit ‘Berkut’ violently dispersed the peaceful protest in Kyiv. The police open and enormous violence against students shocked Ukrainians. Within next days, mass protests demanding Yanukovych’s resignation spread across the country. It was not already solely the question of Ukraine-EU Association Agreement.

To understand the dynamics of the protests we should keep in mind Ukraine’s ability to avoid mass violence even during political conflicts since the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. Many who came later to protest during the winter of 2013-2014, stand not so for European integration, but for a dignity and against violations of their basic human rights by the Ukrainian authorities.

Survey among participants of protest on the Maidan were conducted in December 2013 by the Fund "Democratic initiatives named Ilko Kucheriv" and the Kiev International Institute of Sociology6.

Among the reasons that led people to the Maidan, the three most common were:

• brutal beatings of protesters on Independence Square on the night of 30 November, repression (70%);

• refusal of Viktor Yanukovych to sign the Association Agreement with the European Union (53.5%);

• and the desire to change Life in Ukraine (50%);

• also were expressed desire to change the authority in Ukraine (39%).

The main requirements made on the Maidan, the greatest support (more than half) of the interviewed participants of protests on Maidan were:

• the release of arrested participants of the protest, end the repression (82%);

• the resignation of the government (80%);

• the resignation of Viktor Yanukovych and early presidential elections (75%);

• the Association Agreement with the European Union (71%).

Only 5% of the participants came to protest because of calls of opposition parties. The composition of Euromaidan was very diverse and represents of all Ukrainian regions as well as different social and demographic groups.

The Euromaidan protests, where took part both Ukrainian and Russian speakers, showed that language issue itself is not a dividing line in Ukraine. According to the poll conducted by the Kyiv International Institute of Sociology among the Maidan participants, more than half were Ukrainian speaking, as many as 27 per cent spoke Russian and 18 per cent both7. The Maidan functioned in two languages simultaneously, first of all, because Kiev is a bilingual city.

A survey conducted by the Research & Branding Group in December 20138 found that almost a half of Ukrainians (49%) support the Euromaidan protests in Kiev, at the same time almost the equal number of respondents (45%) have the opposite opinion.

Opinions were divided on a regional basis. Euromaidan protest was mostly supported in the West (84%) and in the Centre (66%) of Ukraine, also 33% of residents of the southern and 13% of residents of the eastern region support Euromaidan as well. While majority of respondents in the east (81%) and south (60%) of the country were strongly against of Euromaidan. But also, 27% of residents of the central and 11% of residents of the western regions did not support protesters as well.

‘Reset of system’

The totalitarian style of laws introduced on January 16 with violation of any legal procedure, transformed the peaceful protests into a mass protest movement and brings violent struggle on the streets. Millions of people who had joined the peaceful protests were immediately transformed into criminals.

Repression against protesters has unfolded rapidly throughout Ukraine. Unwillingness of Yanukpvych`s regime to solve situation in peaceful way and violence against people has provoked growing radicalism of some protesters.

Additionally, Moscow pressed Yanukovych to clear Kiev of protesters in order to receive loan. Then followed the mass murder on the streets in Kyiv the Yanukovych`s regime failed. The violence was so unbelievable and unacceptable for Ukrainian society that even loyal to Yanukovych politicians from Party of Regions quickly changed the side.

The violent actions of Yanukovych`s regime and the Russian intervention in the Crimeaand eastern parts of the country broke Ukrainian tradition of non-violent resolution of political controversy. Russian intervention that accompanied the Yanukovych regime’s fall has produced an existential crisis of Ukraine as a state.

Russia tried to justify annexations of Crimea and aggression on Donbas using the myth of protection of Russian-speaking citizens of Ukraine. At the same time, according to the survey carried in all regions of Ukraine (including Crimea and Donbas) conducted by the International Republican Institute, only 12 % of population (Definitely yes - 5%, Rather yes – 7 %), answered yes on the question “Do you feel that Russian-speaking citizens of Ukraine are under pressure or threat because of their language?” in March 2014. Similarly, on the question “Do you support the decision of the Russian Federation to send its army to protect Russian-speaking citizens of Ukraine?” near 13 % of population answer positively (Definitely yes - 7%, Rather yes – 6 %).

The study of Bruce Etling9 from Harvard’s Berkman Center for Internet and Society, suggests that Russian-speaking Ukrainians may be significantly more supportive of Kyiv’s standoff against Russia and the pro-Russian ‘separatists’ in Donbas.

The differences between Euromaidan 2013-2014 and the Orange Revolution

The main difference between Euromaidan and the Orange Revolution, that political protest in 2004 were organized and led by the oppositional political parties. It was typical elite`s split.

At the early stage, Euromaidan was initiated and organized by the young people and representatives of civil society as a demonstration of the pro-European aspirations. They tried to limit the participation of political parties in their protest. The political opposition only joined the protest later after the cruel violence demonstrated by the authority on 30th of November 2013. Political opposition in Ukraine at that moment was quite weak and also suffered from low level of trust and support. Because in the eyes of many Ukrainians, opposition and the authorities had the same genetics and were deeply interconnected.

So, on the contrary with previous Orange Revolution, Euromaidan was the mass protest movement from the ‘down’ and was not initiated (however supported) by the political elites. It can explain to some point the ‘resistance’ of political system against of real reformation after Euromaidan revolution.

The second point is that the Orange Revolution had a clear political goal and leadership. The Euromaidan had various goals, which are changed in time and there was not one center of decisions making.

Another important point was struggle between generations. Many of protesters on the Maidan were ‘generation of independence’ and they had no already the ‘Soviet’ mentality. Many activists called Euromaidan as the ‘revolution of dignity’. We should stress also the role of new media and social technologies and the growing use of the Internet among population of Ukraine.

The last point is that Ukrainian civil society in 2013 was much more mature and strong. And the main claim of active Ukrainians was the changes of entire system, and not only politicians. Because the Orange revolution was a successful protest against cruel manipulation during Presidential election, but it did not change the political, economical and social order.

According to Olga Onuch, the Euromaidan revolution differed significantly from the Orange Revolution in five ways. “First, the 2013 protests were more widely distributed across Ukraine than those of 2004 […] Second, student and activist groups were strong and prepared in 2004, but not so in 2013 [...]Third, unlike in 2004, in 2013 no one leader emerged to serve as the opposition’s standard-bearer. Instead, the EuroMaidan took the shape of a “coalition of inconvenience” formed by liberal, social-democratic, and right-of-center opposition parties. Fourth, the Yanukovych regime, unlike the Kuchma regime nine years before, did not shy away from using violence to squelch the protests. Fifth, foreign governments and organizations found it hard to broker any deals between the two sides10.”

Myth of two Ukraine

After collapse of Soviet Union Ukrainian society faced the problem of building not only the new state institutions but also a new type of common national Ukrainian identity within the boundaries of one state. One of the complications in post-communist development of Ukraine, with its uncertain perception of itself and absence of common vision of its future, are results of two factors: Ukraine’s historical lack of a unified society and its very short period of statehood. The legacies of stateless existence and the large-scale linguistic and cultural Russification and Sovietization have strongly influenced post-Soviet Ukrainian nation-building. The Soviet national policy of internal “multiculturalism” was in fact a policy of Sovietizations.

It is already a common view that there are two main geopolitical and cultural orientations in Ukraine, two poles: the European or pro-Western one and the pro-Russian, which can also be perceived as pro-Soviet.

The principal mistake of this myth of ‘two Ukraine’ is that it equates language, political orientation and national and regional identity of all Ukrainian citizens. Of course there are some correlations between the preferred language, region of residence, electoral behavior, and views on foreign policy. However, it does not mean that the dividing lines are so definite and unequivocal as the discourse of two Ukraine’s would suggest. We claim that the dividing lines of Ukraine are not geographical, but rather social or determined by age (generational). Despite some regional determinations the main dividing lines in Ukrainian society base not so on the regional identities, but mainly on the social, generational and, first of all, on values or (we can call it worldview) differences.

For instance, as reported by the Democratic Initiatives Foundation, young people of Donbas and Crimea, where generally a negative attitude towards EU membership prevailed, did not differ from their peers in other regions of Ukraine. Within the age group 18-29, we can observe in this region that support of EU membership is 51%, while the percentage of non-supporters is 22%.

Table 4

Should Ukraine join the EU? (All Ukrainian surveys, December 2011)

Source: Ukrainian Sociology Service11

Although the political attitudes of the populations of different regions differ, there are also differences not only between East and West, but also between many other Ukrainian regions. It does not mean that the preferred language determines ethnic and national identity or geopolitical choices.

I would prefer to stand alongside the later works of Mykola Riabchuk, who also stressed that “Ukraine’s main domestic controversy is not about ethnicity, language, or regional issues, as Western reporters and, sometimes, scholars tend to believe. The controversy is primarily about values and about national identity as a value-based attitude toward the past and the future, toward “us” and “them,” toward an entire way of life and thought, symbolic representation and mundane behavior12.”

I would argue that the main dividing line in Ukraine is laid on the level of values and choice of European Ukraine vs Soviet Ukraine. The version of a democratic and ‘European’ Ukraine is conflicting on the very basic value level with a version of ‘Soviet’ Ukraine. Consequently, the main conflict lines are on the level of the identity of Ukrainian citizens, values and their vision of future of Ukraine.

It means that dividing Ukraine as ‘pro-Russian’ (which means anti-Ukrainian or anti-European) and ‘pro-Ukrainian’ (means anti-Russian but pro-European) – is a strong simplification. We could rather argue that, there are competitions between ‘Soviet’ mentality and orientations, which translate all typical Soviet (and nowadays Russian) narratives towards history, identity, foreign policy etc., and ‘Ukrainian’ with all its differences and contradictions. Traditionally, ‘pro-Ukrainian’ was mainly associated with national discourse on Ukrainian identity. However, it would be a wrong idea to interpret such discourse only in a ‘nationalistic’ way, because very often it includes the ‘European’ components in the searching of Ukrainian identity.

As I wrote before, Euromaidan revolution – it is a logical continuation of the deep social and political transformations that began in Ukraine in 1991, but were not finished with establishments of real democratic system. In this sense, Euromaidan – it is manifestation of the classical social and democratic revolution.

Ukraine had long history of political protests: in 1990 was the student “Revolution on Granite”, in 2001- mass protests called “the Ukraine without Kuchma”, in 2004 - the Orange Revolution, and in 2013 - Euromaidan. They have the same genetics, associated not only with the approval of Ukraine as a sovereign state, but above all, with the final completion of the Soviet era, and the elimination of the remnants of totalitarianism.

Abstract

What does it mean “the crisis” in Ukraine in 2013-2014? Is it a new geopolitical battle between ‘East’ and ‘West’ only? Or it is the end of ‘post Soviet’ Ukraine?

There are two dimensions of possible discussions: first, from geopolitical perspective – Ukraine as a battleground between Russia and the ‘West’. Much of the coverage portrays the Ukrainian Euromaidan revolution 2013-2014 as a resurgence of the Cold War - a battle between ‘East’ and ‘West’. The second, Ukrainian Euromaidan – is the end of post Soviet transformations and was the natural protest of Ukrainians against authoritarian rules of President Yanukovych.

I would claim that the main reason of Euromaidan protests in 2013-2014 was an unfinished Ukrainian transformation from ‘post-Soviet’ state toward a real democratic and independent Ukraine. It was a threefold revolution: democratic – in the sense of protests against cleptocratic and oligarchic regimes of Victor Yanukovych; anti-colonial – in the sense of struggle for real independence from Russia; and value revolution – in the sense of struggle of European Ukraine vs Soviet Ukraine, which are differing on the basis of relations towards state, sovereignty and the past. Was it really ‘revolution’ or not – we will see soon, according to results and prospects of reforming of Ukrainian political system.

References

- Etling, Bruce. Russia, Ukraine, and the West: Social Media Sentiment in the Euromaidan Protests. Harvard’s Berkman Center for Internet and Society.

- Kudelia, Serhiy. The house that Yanukovych built. Journal of Democracy, Vol. 25, N° 3 July 2014.

- Levitsky Steven, Way Lucan A. “Elections without Democracy: The Rise of Competitive Authoritarianism”. Journal of Democracy, Vol. 13, N° 2, April 2002.

- Motyl, Alexander. Watching Yanukovych's Mafia Regime Squirm. World Affairs.

- Onuch, Olga. Who were the protesters? Journal of Democracy, Vol. 25, N° 3, July 2014:44-51.

- Riabchuk, Mykola. Cultural Fault Lines and Political Divisions. In: Zaleska Onyshkevych L., Rewakowicz M. (eds.), Contemporary Ukraine on the cultural map of Europe, M.E. Sharpe Inc., New York, 2009.

- Wolczuk, Kataryna. Ukraine and its relations with the EU in the context of the European Neighbourhood Policy. In: Fischer, Sabine (Ed.) Ukraine: Quo Vadis?, Chaillot Paper, N° 108, EU Institute for Security Studies 2008.

- Zolkina M. European integration of Ukraine: experience of yesterday for development of tomorrow. Ilko Kucheriv Democratic Initiatives Foundation, Public Opinion, N°13, 2013.

- 1. Levitsky Steven, Way Lucan A. “Elections without Democracy: The Rise of Competitive Authoritarianism”. Journal of Democracy, Vol. 13, n° 2 April 2002:63.

- 2. Kudelia, Serhiy. The house that Yanukovych built. Journal of Democracy, Vol. 25, N° 3, July 2014:21.

- 3. Motyl, Alexander. Watching Yanukovych's Mafia Regime Squirm. World Affairs.

- 4. Fund “Democratic Initiatives”, 17-23 May 2013;

- 5. Wolczuk, Kataryna. "Ukraine and its relations with the EU in the context of the European Neighbourhood Policy". In: Fischer, Sabine (Ed.) Ukraine: Quo Vadis?, Chaillot Paper, N° 108, EU Institute for Security Studies 2008:96

- 6. Fund Democratic initiatives, “Maydan-2013: hto stoyit, chomu i za shcho?”.

- 7. Kyiv International Institute of Sociology ‘Maidan-2013: Who protests, why and for what?’, poll conducted on 7-8 December 2013.

- 8. Survey by the Research & Branding Group was hold from 4 to 9 of December 2013.

- 9. Etling, Bruce. Russia, Ukraine, and the West: Social Media Sentiment in the Euromaidan Protests. Harvard’s Berkman Center for Internet and Society.

- 10. Onuch, Olga. Who were the protesters?, Journal of Democracy, Vol. 25, n° 3, July 2014:46.

- 11. Public opinion poll was conducted by the Ilko Kucheriv Democratic Initiatives Foundation together with Ukrainian Sociology Service in December 2011.

- 12. Riabchuk, Mykola. Cultural Fault Lines and Political Divisions. In: Zaleska Onyshkevych L., Rewakowicz M. (eds.), Contemporary Ukraine on the cultural map of Europe, M.E. Sharpe Inc., New York, 2009:27.