Home>Is Energy Poverty Getting Worse? Reflections on the Health Crisis

01.02.2022

Is Energy Poverty Getting Worse? Reflections on the Health Crisis

Interview with François Bafoil, Ferenc Fodor and Rachel Guyet

The COVID 19 crisis has both revealed and exacerbated acute inequalities among households in terms of access to energy. In addition, energy prices have been soaring since September 2021 and this has further aggravated inequalities between the wealthiest and the most vulnerable populations. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on a global scale in 2021 has convinced the members of the Energy and Cohesion: Governance, Regulations and Negotiations research group at the CERI to assess and understand the impact of this pandemic at different sectorial and governance levels? The following is an interview with François Bafoil, Ferenc Fodor and Rachel Guyet, scientific coordinators of the research group.

How do you define energy poverty?

First of all, we must identify the differences between developed and developing countries in access to energy. In the latter, energy poverty is the lack of physical access to energy. According to Tracking SDG7: The Energy Progress Report (2021) , “the number of people without access to electricity fell from 1.2 billion globally in 2010 to 759 million in 2019.” Yet this does not include the 2.6 billion people with no access to clean cooking in 2019 and who may be affected by respiratory diseases because of the smoke generated by their traditional cooking devices. 1.5 million people die every year prematurely due to indoor pollution in the home. In addition to the problem of physical access to energy infrastructure, the cost of energy makes power consumption unaffordable for many people. The possibility of physically accessing electricity is therefore not necessarily equivalent to consumption capacity.

In Europe, energy poverty is understood as a situation where a household cannot meet its domestic energy needs, in winter as well as summer. According to the third report of the EU Energy Poverty Observatory, 33.8 million households (i.e. 6.6%) in the EU (28 Member states) were unable to pay their energy bills in 2018 and lived under the threat of a power cut. In addition, 37.4 million households (i.e. 7.3%) said they were cold at home. In many cases, households are forced to go without other essential goods and services in order to pay their electricity bill, a situation that puts their physical and mental health at risk. Clearly, Europeans are not the only ones affected by energy poverty. These figures illustrate the importance of a phenomenon whose causes are to be found in the macro-economic system and in the inability of governments to develop public policies that prevent energy poverty or address it in a systemic way.

What have been the effects of the COVID pandemic on households struggling with energy poverty?

From the outset of the health crisis in 2020, many governments opted for a solution to protect people from the spread of the virus that is unprecedented in modern times: lockdown. These decisions revealed the deep inequalities that already existed in society, particularly in relation to housing access, the quality of which affects the level of energy consumption. The decision to close down businesses and lay off a large number of employees due to the economic slowdown, which have led to lost income for many, have increased the weight of energy expenditure in household budgets. A study entitled Living, Working and COVID-19 conducted by Eurofund (the European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions) between April and July 2020 within the European Union shows that one person out of ten said they were confronted with overdue bill payments—a figure that was higher among the unemployed. In France for example, energy bills were expected to rise between 5 to 7% because of the first lockdown.

Today, the health crisis is coupled with an unprecedented crisis in energy costs. The World Bank has forecast that energy prices will rise by 80% globally in 2021, compared to the previous year. The increase in demand generated in particular by economic recovery programmes is not unrelated to this. These increases are likely to have a severe impact on the 80 million or so European households who, even before the energy price crisis, were already spending twice as much as average on energy. The most vulnerable are therefore likely to be hit hardest by these price increases.

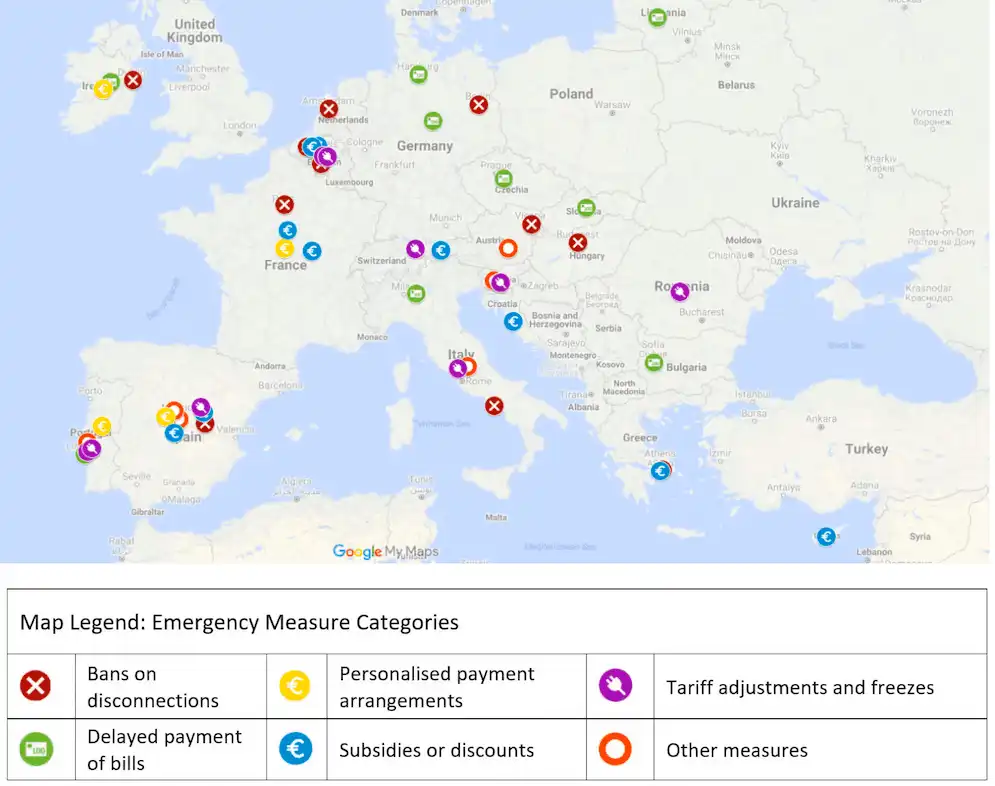

Access the online and updated version of the map here

A group of four researchers, members of ENGAGER—a European research network on energy poverty—have mapped the emergency measures undertaken by national governments and companies to guarantee continuous access to energy during lockdowns, beginning in 2020 at the early stages of the pandemic. This global data collection is based on official government announcements. The list of measures collected is therefore not exhaustive, because it depends on access to information. As can be seen from the map presented above, there may be no measures listed for a particular country but this does not mean that none have been implemented: some countries have policies enforcing a winter halt on power cuts or social transfers, in place since well before the pandemic. The map of Europe shows that the majority of member states decided to ban power cuts as a matter of urgency, sometimes also introducing a cap on tariffs. In many cases, individual payment plans and deadlines have helped to ease the burden of energy bills. However, these measures were temporary and may have led to a build-up of arrears during this protected period, which in turn may have caused further hardship for vulnerable households when they were lifted.

What are possible solutions to reduce energy poverty in relation to this dual crisis?

A consensus emerged among EU member states during the lockdown period, to put in place measures to ensure that all households have access to essential energy services. There are three main categories of emergency responses from governments: a ban on power cuts; action on energy prices to compensate for increased consumption; and offers to defer bill payments, or more flexible and personalised payment arrangements for those facing financial difficulties prior to or as a result of the lockdown.

These temporary measures, which aimed to mitigate the shock of the health crisis, revealed the crucial importance of access to energy in everyday life. The current crisis in energy prices is different because it is the result of the way the market works and the global increase in gas demand. National governments have been more or less reluctant to intervene and the measures to support the poorest groups in society are mainly financial (cash transfers or temporary reduction of taxes usually levied from the energy consumption bill). The rise in energy prices has prompted the European Commission to introduce a “toolbox” for action and support that endorses responses already undertaken at the national level, and encourages member states that have not yet introduced support programmes to do so in compliance with European rules.

While the current crisis makes energy poverty a central issue for national public policies and the European Green Deal, it also raises the question of the European Union’s ability to mitigate the effects of price rises on households in the short term, but also to prevent energy risks in the long term. It is all the more crucial to anticipate the energy risk as European climate action will contribute to increasing the cost of electricity and heating production through the taxation of CO2.

The conclusion is that while climate action is necessary, it must be accompanied by sustainable protection measures for the poorest households. Soaring energy prices have put the importance of social justice in the energy and climate sectors back on the European agenda, but this is far from resulting in a consensus.

According to you, what are the long-term questions that need to be addressed?

There are three particularly acute issues we want to mention, although they are not the only ones and the debate will continue.

The question of redistribution is undoubtedly the first to emerge, for the reasons just given, and in particular due to inequality of access to electricity, poor housing, the increase in energy needs, but also growing demand due to the proliferation of devices connected to the internet. The scissor effect resulting from the growth in demand and the loss of income can only be compensated for by the intervention of the state and companies in favour of greater solidarity. On this basis, the question we raise is: is it possible to reconceptualise the return of the state to the energy sector in order to guarantee a form of public service in energy?

The second issue is that of governance, i.e. the form that this return of the state as a central player in energy could take, but through a renewal of partnerships with both the regions and economic operators. What division of labour should be envisaged? What place should be left to civil society - on a national and international scale? As we can see, seeking to integrate the consequences of the pandemic forces us to deepen our thinking on governance and to question the state’s capacity to ensure security, peace, sustainability, and redistribution. But we must also look at the experience and failure of competition in the energy sector (with the unfulfilled promise of lower prices). These elements also help justify the return of the state.

Finally, the social acceptance of the European climate and energy policy by citizens requires a fairer distribution of costs and benefits between the “losers” and the “winners” of the energy transition. But how will European ambitions be financed? Will citizens still be able and willing to participate? Citizens who are able to invest in renewable installations (especially solar panels) can produce their own energy and thus protect themselves from price increases. Will the current energy price crisis reinforce such goals in the population?

What solutions can be implemented to extend this form of energy autonomy, which is expensive and therefore inaccessible to many?

It is possible to imagine that the EU’s climate policy will only be socially and politically accepted if citizens are involved in the decision-making processes and in production systems. This might take place for example through renewable energy communities formed as legal entities, under the revised EU Directive on Renewable Energy (2018/2001 REDII), bringing together members (citizens, local authorities, SMEs) who decide to invest in renewable energy in order to produce economic, environmental and social benefits to its members and/or the community.

Such issues will remain on the public policy agenda for a long time to come and will constantly intersect with other equally important and unavoidable questions concerning innovation and investment, which can now only be thought of in relation to the requirements of an ambitious climate policy.

The “Covid, vulnérabilités et crises de la démocratie” project (1 April 2021-31 December 2022) is part of a collaborative research programme between the CERI and EDF R&D that has lasted for more than a decade, and which has studied issues as varied as energy poverty, energy justice, climate change, and energy transition. It also explores links between populism and energy redistribution politics, which are at the heart of several of the books published by the research group. The importance of the COVID-19 pandemic on a global scale in 2021 pushed the members of the project to integrate their work into the vast research trend seeking to understand and assess the impact of this pandemic at the level of actors, professions and employment sectors, as well as territories. The consequences of the pandemic on the most vulnerable households and individuals present a challenge to our welfare state models and their ability to respond effectively to increasing inequalities between citizens. But it is not just about developed countries. The least developed states are suffering just as much from difficulties in accessing electricity as a result of the pandemic. We must therefore reflect on the local “solutions” developed to deal with these disparities in access and use, but also on the ability of energy companies to deal with payment defaults. In addition, and still related to energy poverty, there is the risk of rising electricity prices, particularly as a result of the closure of coal-fired power stations, which we intend to address in our final seminar. The end of coal is in fact part of the European climate and energy policy that aims to make Europe the first carbon neutral region by 2050. This is what the EU Green Deal proposed by the Commission in 2019 aims to achieve by encouraging the reduction of carbon emissions in transport, energy, agriculture, industry, etc. It has led to the development of the “Fit for 55” package of initiatives, a series of climate legislative proposals aimed at reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 55% by 2030. Aware that this transformation is likely to be painful for many people (coal workers, consumers, and inhabitants of regions in transition), the Commission announced in 2021 the creation of a Social Climate Fund, which is designed to cushion the social and distributive impacts of the climate and energy change. The central concern therefore remains the goal of a fair energy transition that ensures that no one is left behind.

References

François Bafoil, Ferenc Fodor, Rachel Guyet, Dominique Le Roux, Accès à l’énergie, les précaires invisibles, Presses de Sciences Po, 2014.

François Bafoil, Ferenc Fodor, Rachel Guyet, « Penser la justice énergétique en Europe et en Asie (Energy and Justice in the EU and in Asia), L’Europe en formation, 2015/4 (n° 378).

François Bafoil, Rachel Guyet, "Fighting Energy Poverty," Cogito, July 2019.

Access further publications by Energy and Cohesion: Governance, regulations and negotiations

Interview by Corinne Deloy.

English version by Miriam Périer and Katharine Throssell.

Follow us

Contact us

Media Contact

Coralie Meyer

Phone : +33 (0)1 58 71 70 85

coralie.meyer@sciencespo.fr

Corinne Deloy

Phone : +33 (0)1 58 71 70 68

corinne.deloy@sciencespo.fr