Yemen, ten years of war. Interview with Laurent Bonnefoy

In March 2015, the Saudi-led military coalition bombed Houthi rebel targets for the first time: this was considered as the beginning of the Yemen war. Ten years later, the conflict has not ended, and in mid-March 2025, Donald Trump decided to significantly increase US military involvement and announced a new operation. Beyond the geopolitical and regional issues and the serious humanitarian consequences, the conflict has undeniably disrupted the Arabian Peninsula as well as Yemeni society and institutions. Laurent Bonnefoy reminds us why it is important that research does not turn its back on this conflict. Read our interview.

Yemen, a country you are very familiar with, has been at war for ten years. Can you remind us, in a few lines, of the origin of this conflict?

As opposed to the simplistic discourse of the belligerents, social science approaches generally shed light on the complexity of the factors and origins of a war. The conflict in Yemen is often hastily perceived as a sectarian war between Shiite rebels allied with Iran - the Houthis - and a Sunni government supported by Saudi Arabia. Both the religious and regional dimensions are indeed present, and the war is usually dated to the start of the military operation by the Saudi-led coalition on Houthi positions on the night of 25 to 26 March 2015.

However, the chronology is the subject of heated controversy. Many Yemenis, hostile to the Houthis, point to 21 September 2014, which corresponds to the rebels' capture of the capital, Sana'a, and marks the beginning of their coup d'état. This account highlights a more local dimension of the conflict, distinct from the Iranian-Saudi rivalry that has given the Yemeni war a regional dimension. Thus, the latter is mainly the result of competition between political elites in a context of poorly negotiated transition following the ‘Yemeni Spring’ that began in 2011. The rebels were able to build up their military capacity and carry out their takeover because they allied themselves with the former president who had been deposed by the revolutionaries, seeking revenge.

Are the implications of the conflict the same today?

Obviously, a decade of war has turned Yemeni society upside down. Understanding these changes is a key issue for researchers. Ten years is a long time, especially because services, particularly education, have collapsed and a generation seems to have been sacrificed. The effects are also significant in religious terms, and remain largely under-analysed even though the Houthis have transformed and polarised identities. The Salafis have also engaged in militarisation, often abandoning their supposedly apolitical and pacific approach. The issue of access to the field, which has been made very difficult if not impossible for foreign researchers and Western journalists alike, makes our collective understanding of the situation more complicated, including for Yemeni colleagues, some of whom live in exile.

At the same time, it can be said that the issues at stake in the conflict have changed, particularly in relation to the regional dimension. On the one hand, the Saudis have implicitly recognised the ineffectiveness of their military strategy. Since the spring of 2022, they have been trying to withdraw from the Yemeni quagmire, without really succeeding. They are thus acknowledging that the Houthis are a legitimate interlocutor whose control of a significant part of the territory they no longer openly contest. This development has been accompanied by a significant improvement in Iranian-Saudi relations.

On the other hand, the issue of regional rivalries has shifted and tensions are rising between the Saudis and their main ally in the coalition, the United Arab Emirates. Over the course of the war, the UAE has established a partnership with the southern secessionist movement, undermining the authority of the government recognised by the international community. This is a challenge in the Gulf that is still too neglected.

Finally, the position of the Yemeni conflict was suddenly turned on its head in the wake of the 7 October attacks in Israel. Indeed, the Houthis, asserting their support for the Palestinians, have been developing a new strategy since November 2023 by attacking merchant shipping in the Red Sea. The unexpected effects have led to a reduction of more than 50% in maritime traffic in this important route for world trade. More than a hundred ships have been affected, including one that was sunk, while huge oil spills have been narrowly avoided. The Houthis have thus demonstrated the capacity of their movement to cause damage as well as the need to resolve the conflict. Donald Trump's decision in February 2025 to classify this movement as a terrorist organisation and to initiate, in partnership with the British and Israelis, new bombings of Yemen, runs counter to the advice of many humanitarian aid workers on whom two-thirds of Yemen's 35 million inhabitants depend. USAID's funding cuts also raise fears of a significant deterioration in the humanitarian situation.

Who benefits from the war?

It has become clear over the years that the war mainly benefits the Houthis. Their interventions in the Red Sea have enabled them to acquire a certain popularity at the regional level. Indeed, they skilfully present themselves as the only supporters of the Gazans, at a time when the Arab states have lost much credibility. By being the target of Israeli strikes that have destroyed civilian infrastructure, notably the port of Hodeida in the Red Sea, they have positioned themselves as an alternative to Hezbollah, at least symbolically. They have managed to send drones and missiles that have occasionally hit Tel Aviv, even claiming a casualty. The American bombings ordered by Donald Trump on 15 March 2026 killed dozens of civilians and fuelled the same logic of a movement that, alone against all, challenges the international order. In addition, the Saudi government's desire to leave the Yemeni theatre of war from 2022 has put the Houthis in a favourable position. They are therefore upping the ante and seem willing to humiliate the Saudis even more before signing any peace agreement.

One may wonder how to continue to keep hope and a form of optimistic commitment... Can it be interesting, then, to turn to the arts and creation?

I ndeed, at the end of a decade full of war, the question of researchers' weariness in the face of their subject engaged in a desperate spiral of destruction obviously arises. The sensitive part of our work, based on an emotional relationship to the field and to those we work with there, is undeniably called into question or at least increasingly reduced to “sad passions”. Injured or killed interlocutors, those who are trying to flee and who must be helped, friends whose positions leave us puzzled: war also affects those whose job is precisely to analyse conflicts. The destruction of heritage, through bombing as well as the resulting economic crisis, is another source of pessimism. It is not always easy to find something to hold on to, but the arts and creativity are part of it.

ndeed, at the end of a decade full of war, the question of researchers' weariness in the face of their subject engaged in a desperate spiral of destruction obviously arises. The sensitive part of our work, based on an emotional relationship to the field and to those we work with there, is undeniably called into question or at least increasingly reduced to “sad passions”. Injured or killed interlocutors, those who are trying to flee and who must be helped, friends whose positions leave us puzzled: war also affects those whose job is precisely to analyse conflicts. The destruction of heritage, through bombing as well as the resulting economic crisis, is another source of pessimism. It is not always easy to find something to hold on to, but the arts and creativity are part of it.

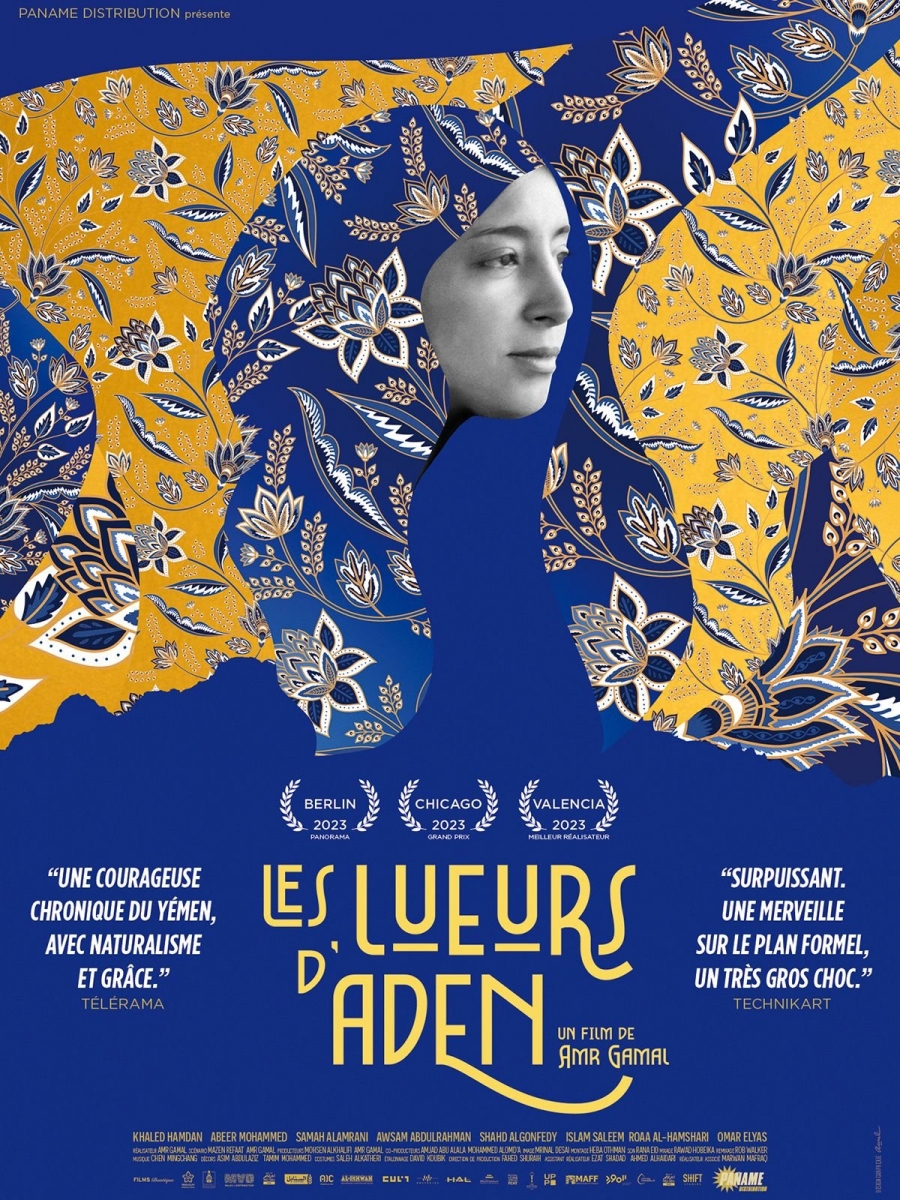

For example, on 1 April I will have the pleasure of taking part in the presentation of the film Les lueurs d'Aden (The Burdened) by Yemeni director Amr Gamal, shown as part of the cinéclub du CERI with the cinema L'entrepôt in Paris. Despite the difficult subject of the film, I find a kind of comfort in such creativity.

Moreover, I admit that there is also a valuable dimension to the feeling of being part of an epistemic community that, while having avoided the great political tensions inherent in a situation of conflict, has been working together for many years and shares a common interest in and respect for the future of Yemen. I also find a degree of satisfaction in the fact that the war, despite the horrors, has also encouraged the emergence of a new generation of Yemeni researchers. We will have the pleasure and interest of listening to some of them during a day-long seminar organised by CERI/Sciences Po, in partnership with the journal Orient XXI and the Chair of Religious Studies, on 26 March, devoted to ten years of war in Yemen.

Interview by Miriam Périer, CERI.

Info & registration to the 26 March seminar

Info & booking for the 1st April cinéclub at L’Entrepôt

Further reading:

- Laurent Bonnefoy, Yemen and the World. Beyond Insecurity. London, Hurst/OUP/CERI, 2018.

- Laurent Bonnefoy, “Revolution, War and Transformations in Yemeni Studies ”, Middle East Research and Information Project: Critical Coverage of the Middle East Since 1971 , No. 301, 2021.

- Revolution, War and Transformations in Yemeni Studies - MERIP

- Abdullah Hamidaddin, The Huthi Movement in Yemen: Ideology, Ambition and Security in the Arab Gulf , I.B. Tauris, 2022.

- Helen Lakner, “Les houthistes du Yémen sous les feux de la rampe” , Orient XXI, 10 janvier 2024.